by Tracie Griffith

Why a blog on the tracking of Port Fairy’s great white sharks? I’ll get to that later. First it’s worth taking a look at how much we’ve learned about this species in recent decades.

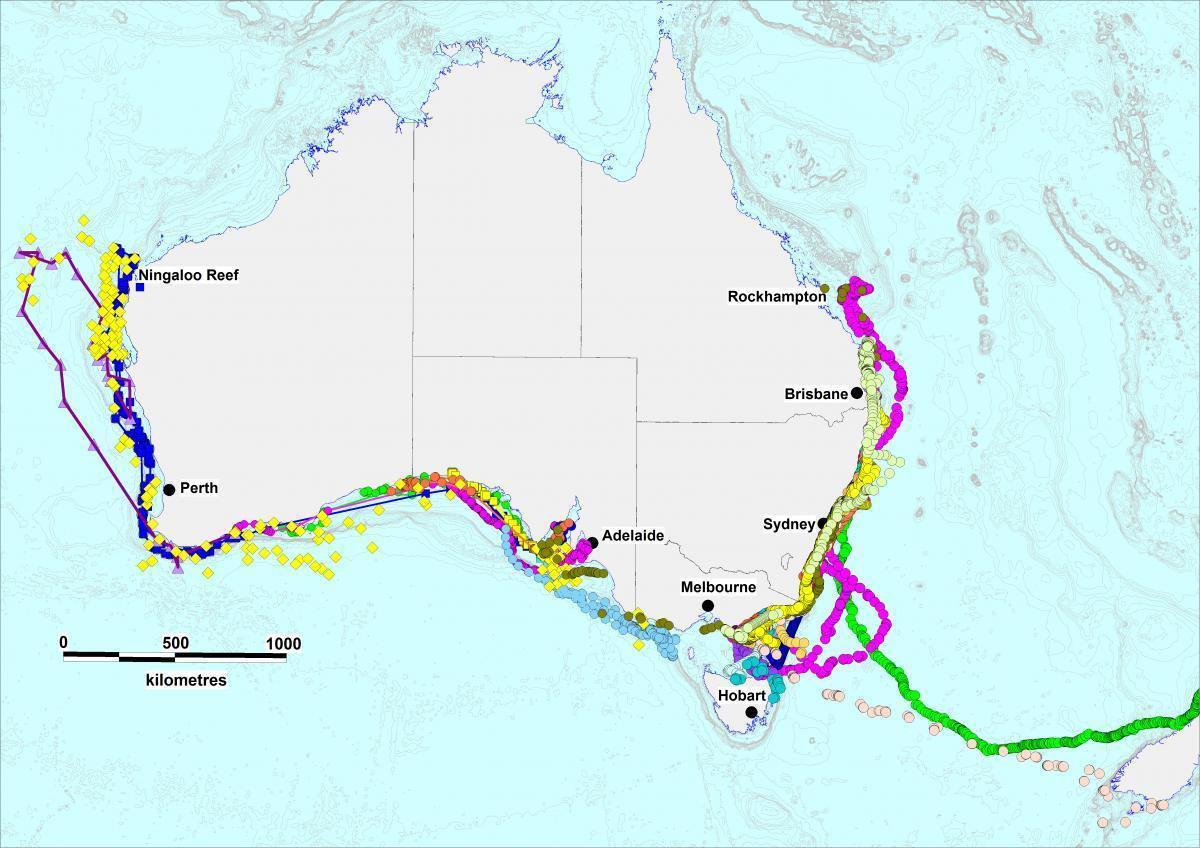

Through genetic testing, scientists have established there are two separate populations of great white sharks in Australia. The eastern population ranges from central Queensland (Rockhampton) to southern Tasmania and the western population ranges from western Victoria to north-western Western Australia (Montebello Islands).

The eastern population has been known to travel as far as New Zealand. On the other side of the continent, a shark named Nicole (after the Australian actress Nicole Kidman) made the first known trans-oceanic migration from South Africa to Western Australia in 2003-2004. Nicole then returned to the same place she started from at Gansbaai, Western Cape, South Africa – a 20,000 km round trip, completed in just nine months.

As you would expect from these findings, the waters surrounding Port Fairy are frequented predominantly by the western population of great whites. So it stands to reason that we should be more concerned about the activities of great whites in South Australia and Western Australia, right? For example: the number of shark attacks along those coastlines; the West Australian Government’s hunt-to-kill measures in response to perceived threats; tagging programs for the western population.

Well, the only thing that is certain about this species is its ability to defy expectations.

Despite the genetic differences, tagged sharks from both populations have shown a healthy disregard for the natural barrier presented by Bass Strait, moving through the strait itself or circumnavigating Tasmania to mingle with great whites on the other side of the continent. Kent Stannard from ‘Tag for Life’ reports that a three metre great white – number 28 – tagged in Ballina in July 2016, travelled through Bass Strait in September of the same year and continued as far west as the Cape Le Grand National Park near Esperance, WA – where it spent the summer months. Shark 28 was picked up on receivers at Lady Julia Percy Island a few months ago, on its return trip past Port Fairy, and at the time of writing, has made it as far north as the Sunshine Coast.

So Shark 28’s movements prove we can’t be completely complacent about what is happening on the eastern seaboard after all.

Ballina was of course the setting for a cluster of nine shark attacks in 2016, resulting in one fatality. WA beaches experienced a more prolonged cluster of shark attacks from 2010-2013, which resulted in seven fatalities. It was this cluster that caused the WA State Government to implement a controversial shark cull in 2014. The cull ran for three months and was called off after failing to capture even one great white. A total of 172 sharks were killed – 163 of those tiger sharks, who have not been responsible for a fatality in WA waters for over 20 years.

Given the extraordinary speed and distance great whites are now known to travel, it is understandable why calls for shark hunts and culls at the site of a recent attack are considered so futile.

The great white was placed on the protected species list in 1999 and efforts to regenerate its numbers are now being blamed for the recent rise in attacks in Australian waters. However, evidence indicates that a rise in the human population is actually to blame. Australia’s population has grown from 3.7 million in 1900 to 24.5 million in June 2017, and ever-increasing numbers of people are engaging in recreational activities in coastal waters. It may be hard to believe, but bathing in the surf was illegal in this country in daylight hours as recently as 1902.

Surf patrols are considered the best way to protect ocean enthusiasts against shark attacks – being far more effective than nets, baited drumlines or culls. To this end NSW, WA, SA and Victoria have introduced shark alert apps that provide up-to-the-minute information on sightings and tracking data. Victorians can access the VicEmergency website at http://emergency.vic.gov.au/respond/ or the Life Saving Victoria website at http://lsv.com.au/life_saving_services/shark-safety/ for further information.

So why a blog on the tracking of Port Fairy’s great white sharks?

Because state-of-the-art tracking systems have taught us more about great white behavioral and migratory habits than previous research methods, and education is the only thing that will save this species from the hysteria of the Jaws generation (thank you Madi Stewart, aka Shark Girl, for this apt description) and the competitive drive to catch the record-breaking specimen.

As an apex predator, great white sharks are naturally low in abundance, but essential to the health of marine ecosystems. They are a long-lived species that matures late and has low fecundity. Female great whites do not reproduce until they are approximately five metres in length, at 18-20 years of age. Knowing this, it is easy to understand how vulnerable the species is to fishing pressures.

And there’s so much more to learn. Research undertaken by the National Environmental Research Program in 2016 failed to locate any great white nursery areas in SA or WA waters. Great white nurseries have been identified on the eastern coastline at Port Stephens in NSW and 90 Mile Beach-Corner Inlet in Victoria. It was thought similar nurseries would be found for the western population of great whites and the targeted areas were the Great Australian Bight (reaching from Esperance to Eucla in WA) and Encounter Bay in SA. Kent Stannard has surmised that a nursery area may exist in Victorian waters west of Bass Strait. Wouldn’t that be interesting?

It was hoped that juveniles in any identified nursery areas in SA and WA could be tagged like they are at Port Stephens and Corner Inlet, to assist with determining the size and trend of the western population of great white sharks.

The CSIRO team formerly led by Barry Bruce – the guru of great white shark research in Australia – pioneered the shark tagging and tracking tools that have become standard practice worldwide. With this kind of ingenuity at our fingertips, hopefully our focus will remain on research and educating the public about this species, rather than a return to mindless killing of what is justifiably an internationally protected species.

Some interesting sources of information on great white sharks for people who want to know more:

The CSIRO website contains the latest scientific information on the great white shark and state-of-the-art tagging programs in Australian waters. The team at the CSIRO was formerly led by Senior Shark Scientist Barry Bruce, a world renowned expert in his field. Bruce’s team pioneered shark tracking technologies and remain at the forefront of international research efforts in support of the species.

https://www.csiro.au/en/research/natural-environment/biodiversity/shark-research

https://www.csiro.au/en/research/animals/marine-life/sharks/white-shark-research-findings

The NSW Department of Primary Industries undertakes a tagging program of great white sharks in collaboration with the CSIRO. The sharks are fitted with external fin-mounted satellite tags and surgically inserted acoustic tags where possible. The movements of the tagged and numbered sharks can be followed on the website.

https://www.sharksmart.nsw.gov.au/

The National Environmental Research Program – Marine Diversity Hub is a collaborative project hosted by the University of Tasmania. Partners include the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences, Charles Darwin University, CSIRO, Geoscience Australia, Integrated Marine Observing System, Museums Victoria, NSW Department of Primary Industries, NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, and the University of Western Australia. The latest science on great white sharks can be found under Theme A: Improving management of threatened and migratory species – Project A3: A national assessment of the status of White Sharks.

https://www.nespmarine.edu.au/theme/improving-management-threatened-and-migratory-species

The Four Corners episode Shark Alarm (8th February 2016) investigates the record number of shark attacks in Australia in recent years, with particular emphasis on the clusters of attacks in northern NSW and WA. The episode features an interview with the CSIRO’s Barry Bruce, the guru of great white shark research in Australia.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-02-08/shark-alarm-promo/7140546

Madison Stewart is otherwise known as ‘Shark Girl’. Madi grew up on a yacht in Queensland and now campaigns all over the world for shark and ocean conservation. Check out her website, Facebook page and the 2017 release of Blue The Film (an Australian documentary). There are many short films by Madi available online – take a look at Hitchen’s Razor (2013), My World (2014) and Obstruction is Justice (2014) for starters. The documentary Shark Girl (2014) on the Smithsonian Channel is a must-see.

https://www.oceanculture.life/ocl/madison-stewart

https://www.instagram.com/sharkgirlmadison/?hl=en

https://www.facebook.com/projecthiupage

Brendan McAloon’s book Sharks Never Sleep (2016) also investigates the record number of shark attacks in Australia in recent years. McAloon provides a timely reminder that surfers are most at risk and every time we enter the ocean we are opting for a wilderness experience. A great read, but be warned, it contains graphic descriptions of shark attacks that may put you off going back in the water forever.

The Australian Shark Incident Database (formerly known as the Australian Shark Attack File) is maintained by Taronga Zoo in Sydney and provides statistics on shark attacks in Australian waters dating from 1791. The site explains the difference between ‘provoked’ and ‘unprovoked’ attacks, and provides detailed state-by-state reports on attacks over the past five years.

https://taronga.org.au/conservation-and-science/australian-shark-incident-database

The International Shark Attack File (ISAF) is based at the Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. The ISAF is a compilation of all known shark attacks worldwide and lists over 4,000 incidents dating back to the mid-1500s. According to the ISAF, approximately 85% of great white attacks have occurred in three regions: Australia, the Pacific coast of the USA and South Africa. The great white is responsible for more human fatalities than any other species and is considered the most dangerous shark in the world.

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/fish/isaf/home/

‘Tag for Life’ is a not-for-profit charitable trust founded by Victorian surfer Kent Stannard. The trust aims to communicate scientific information that supports a safer coastal environment for all users. Funds raised assist the tagging of great whites in Victorian waters. Stannard is also creator of the ‘White Tag’ clothing label. You can support Stannard’s work by donating to his not-for-profit organization ‘Tag for Life’ and purchasing coastal wear from his ‘White Tag’ website. The ‘Tag for Life’ Facebook site provides the latest information on shark movements in Australian tagging programs and world news relating to great white sharks.

References:

Bruce, B. (2016). Determining the size and trend of the west coast white shark population. Retrieved from https://www.nespmarine.edu.au/system/files/NERP%20Emerging%20Priorities%20Project%202.5%20-%20Determining%20size%20and%20trend%20of%20west%20coast%20white%20shark%20population_June2016_Report_1.pdf

Four Corners (Producer). (2016, February 8). Shark Alarm [Television broadcast]. Sydney, Australia: ABC Television.

National Environmental Research Program – Marine Diversity Hub. (n.d.). Towards a national population assessment for white sharks. Retrieved from https://www.nespmarine.edu.au/system/files/NESP-MBH_A3_white-shark_fact-sheet_FINAL_Sept2015.pdf

NSW Department of Primary Industries. (n.d.). Shark 28. Retrieved from http://www.wildlifetracking.org/index.shtml?tag_id=157666 (reference no longer available online)

Paddenburg, T. (2017). Shark migration: great white ‘shark 28’ travels from NSW to WA. Retrieved from http://www.perthnow.com.au/news/western-australia/shark-migration-great-white-shark-28-travels-from-nsw-to-wa/news-story/b380f2a2d907e4d617f3a11a2806acd2

Taronga Conservation Society Australia. (n.d.). Australian Shark Attack File. Retrieved from https://taronga.org.au/conservation-and-science/australian-shark-incident-database

White Shark Trust. (n.d.). Nicole: First Great White Shark Transoceanic Migration between South Africa and Australia. Retrieved from http://www.whitesharktrust.org/migration.html (reference no longer available online)